Dear Misha,

I met you almost thirty years ago. And it is almost thirty years since I last saw you. How long have we spent together? One week?

The evening before we parted I promised never to forget you.

That summer was special for me. My memories of many events during that summer vacation are very vivid. And every time I recall this time, when I for example talk to my Mother or my sister about then, I think about you.

I am finishing reading a deeply touching, a deeply human, both heart-breaking and heart-warming book: “The Kite Runner” by Khaled Hosseini. Maybe you read it? The main characters are boys who grew up in 1970s and 1980s in Afganistan. It is a novel. But it might have been your story. Although, I hope it wasn’t.

Did you know, that we were prepared for your arrival? It was summer 1985. I was twelve, not quite thirteen, years old then.

After my father died in 1983, I was diagnosed with anemia, and my worried mother and sister made everything to put me back on my feet. The trip to this sanatorium was expensive, as well as the black caviar my mother was buying specifically for me because it was known to promote production of the red blood cells. The caviar was like medicine for me at the time. Today, I like the taste of it. It is close to a miracle that my mother could arrange me going to this sanatorium, which was known as one of the best for children in Soviet Union.

And it was the best for me. It was good for my physical health. But it was also good for me in any possible sense. For the first time in my life I learned that I could be taken in any other way than as a crying softie. I was astonished to find out that the girls with whom I shared a room in the sanatorium thought of me as of a rebel, close to a “hooligan”. In the Soviet school times then, the word “hooligan” was secretly considered with admiration and awe. A “hooligan” was an ultimate rebel and leader in the never ending “children-adult” conflict. I was very much surprised and endlessly pleased to be seen as a rebel. Agreeable with the adults at the sanatorium. But a rebel nonetheless. At the end of the stay, after you have already left, I demonstrated my strength to myself. I stood up openly against harassment by some silly boys from our otriad and could look directly into the eyes of the one who thought he was allowed to do anything. Before this encounter, I thought what many of my schoolmates in Moldova thought of me. That I couldn’t stand up for myself. That I ran away, hid and cry. But this summer was different. In every sense of it. It was also a summer what I met a person for a very short time, but who would always be one of my dearest friends.

What were you told before you came to the sanatorium in Crimea that summer? Our group, the pioneer division, otriad, as it was called then, consisted of about twenty children before you and other children from Afghanistan came to join us for a part of our stay. I don’t remember our teacher’s name. But I remember her face. I remember her telling us that she lived in a small town nearby where she worked as a teacher during school time. During summer months she worked with children at sanatorium, and took the role of a class teacher, with exception that instead of lessons we had various medical, health strengthening procedures, sports and leisure activities. And I remember what she said in the evening before your arrival.

She said that there were twenty or thirty of children, originating from Afghanistan, coming to stay with us for a week. She said that most of you were orphans. That most of your childhood in Afganistan consisted of hiding away from bombs, of fear and hunger. That you were now brought up in an orphanage in Tadzhikistan. She asked us not to inquire you on your past, but just let you enjoy the summer and think, even if for a short while, that you had a happy childhood.

The group of children you came with was divided into smaller groups of eight to ten children and assigned to various otriads, which differed by the age of children in them. The teachers guessed that all of you were older than of guessed age, meaning older than us.

The following day we met you. We had the usual gathering in the hall, where we were all seated in a circle or rather rectangular around the walls of the hall. All of you were speaking very good Russian with a very pleasant, as I thought, accent. The softness of your accent sounded familiar reminding me of the accent I heard at home in Moldova. We were told that every one of you has chosen a Russian name, so that we, on the other side, wouldn’t struggle with names unfamiliar to us. Then, you and your friends introduced yourselves, first by telling your original name and then the one you have chosen in Russian.

We all listened with curiosity to names unknown to us and then tried to remember the names you have chosen. As the last from your group has presented himself, we all erupted with laughter. His real name was very long. I thought it contained more than ten words. And then he told us his name in Russian: “Vásea”.

You have chosen the name “Misha”. The name so important to me. The name of my father.

But there was something else that draw my attention to you. I thought I saw you before. I knew this was impossible. But I still had this feeling.

And then I had it. You looked so like my father on a very old picture taken many years before at an orphanage. Like him, you were one of the smallest in the group. Like him, with short shaven hair. With tanned skin darker than of the others around, and with the same serious look.

And like him, you grew up in an orphanage. I was so excited with this similarity and this “connection” that I hurried to share it with you. You seemed to be as excited as I was. You asked me about my father and what he has done in and with his life. I didn’t realize then, what this might have meant for you. Today I see that my father’s story might have given you hope. Hope that an orphan like you could have a bright future.

I remember us being inseparable during your stay at the sanatorium and how we went for sports and common activities together. Was it really only five or six days? With the vividness of the emotions and wonderful experience of our friendship, I have a feeling it was much longer. You were a brother I never had but always wished for.

In the evening before we parted, we watched the closing of Spartakiada, a socialistic alternative to the Olympics. I don’t remember exactly why, but there were only the two of us in the open hall of our otriad, where the TV-set was standing. I think, many went to the bonfire made in frames of a farewell party for you and your friends. Some went to watch the closing of Spartakiada with the elder children from the neighboring otriad. And there we were, sitting side by side and watching the show. I told you how I watched live, at an edge of a highway in Moldova, together with my father, a runner carrying the Olympic fire on its way from Greece to Moscow in summer of 1980. At some point we held each other and cried. We didn’t want to part. There and then we promised never to forget each other.

You left early next morning and I never saw you again.

I don’t know whether you went back to Afghanistan or grew up in the Soviet Union. Or where you might be now. I even don’t know your real name. But I dearly hope that you are happy. Maybe you have a family and children of your own. And if you do, then I am sure that like my father, you do everything to make their childhood as best as it could be, because you want to save them from the fate given to you.

My heart squeezed with pain when I read “The Kite Runner”. With pain and fear that such fate as described in the book could happen to anyone.

I have now a boy of my own. He is three years old. With dark hair, dark eyes, tanned skin, and furrowed eyebrows so similar to my father’s. So much reminding me of you. My heart of a mother wishes that he never endures pain of a war. The pain, which had hit you and my father so hard.

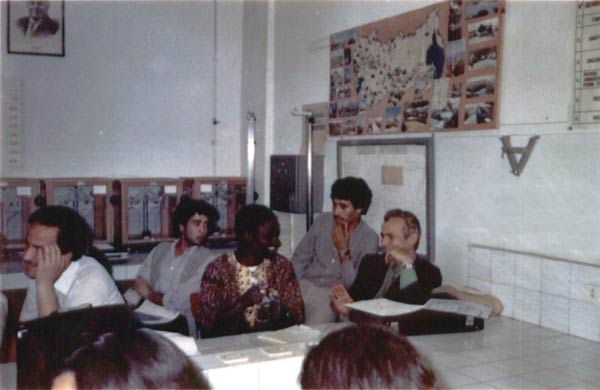

I am aware that you may never read this. And even if you do, you might not be able to recognize yourself in this story. But if you do, then here are two pictures. One of which I told you about so many years ago. The one with my father. Taken on June 10, 1953 in Moldova. And another is of our otriad in summer 1985 in Crimea. It was taken at a morning lineika, translated “ruler”, morning gatherings, where we lined up in pairs, listened to some standard socialistic music, call-outs and propaganda, and then were informed of the events planned for the day. I am sure that in this picture I am turning to check up on you, to see whether you noticed that we have been photographed.

Thank you for crossing my path, Misha! And thank you from all my heart for those memorable and unforgettable days!

With love and affection,

the sister you found during one summer in Crimea,

Vica

My father is the second from the left.

Vasea is the first from the left. You are the second. Another parallel. I am the fifth or sixth from the right, who looks back at you.